Algorithm: Archetype

Christopher Shaw

Northwest African American Museum, Seattle

I could understand why somebody who doesn’t often go to museums would have questions about their experience viewing Algorithm: Archetype, Christopher Shaw’s show at the Northwest African American Museum. It is a fact that most objects we experience are not built to the quality that Shaw’s work boldly and simply presents. He reminds us of our presentist bias when we think of algorithms. In 2020, when the word “algorithm” is evoked in the title of the exhibit, one does not enter NAAM’s Paccar Gallery with clay and stoneware in mind. Even looking at what’s in front of you, you might not allow yourself to see what you’re looking at. Like the mystiques of Old World antiques, whose construction endures, or is unearthed, or in a British museum, pieces in Algorithm: Archetype defy the way we understand value in a contemporary context.

In opposition to antiquity, the most coveted and useful devices are getting lighter in weight and lower in production quality. Our world is cheaper and more disposable than it once was, and how could art not follow suit?

Instead of building from what is exploitable, such as patterns or likenesses, Shaw crafts art pieces that will endure, ascribed to conversations with ancient Nile Valley wonders. It is not a new development. By refusing what is new, Shaw is part of an informal group of contemporary artists who work through the divine art-science relationship in Black cultural production. In that regard, the advantage Shaw has, in working in architecture and sculpture where the benchmark is the Great Pyramids, is that the conversation is clearly not focused on originality. As a seed might, Shaw’s work is imbued with permanence as its model and fate, unconcerned with any notion of originality that disconnects it from its ancestors.

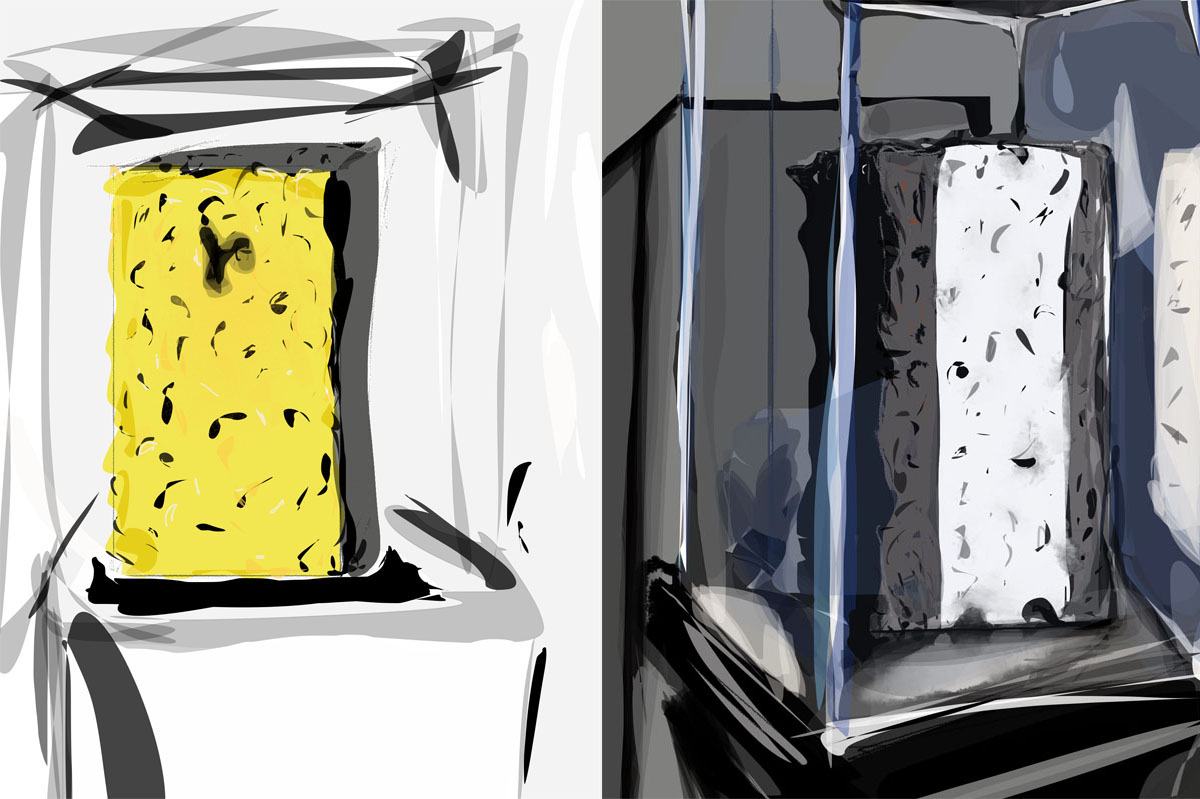

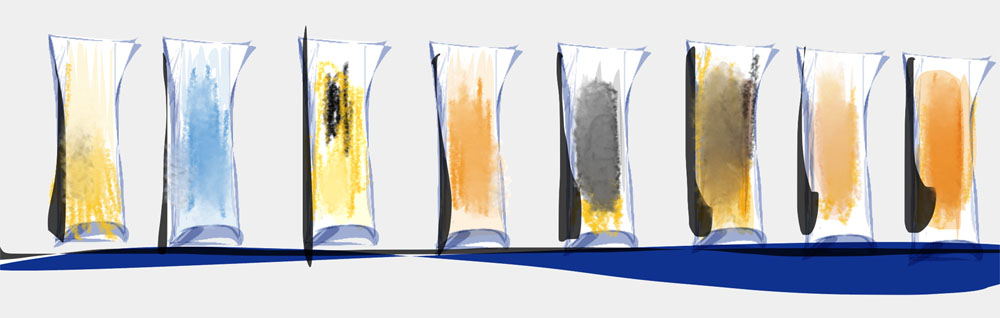

The pieces are arranged sometimes in a collection, sometimes in a series and always raised from the ground. A unique series of two rectangular masses made of stabilized soil bookend the gallery presented in display cases.

In stark contrast, a series of smooth-surfaced single-aperture sculptures as nonporous as vessels can be sat on a low wall protruding into the floor. The range of materials and treatment in the show, as if the installations have different room temperatures, renders stabilized soil as a sort of portrait of melting and stone as if sculpted organically by water erosion.

Shaw used the two primary walls to hang two series of sculptures that carry a range of themes important to the cohesion of the installations.

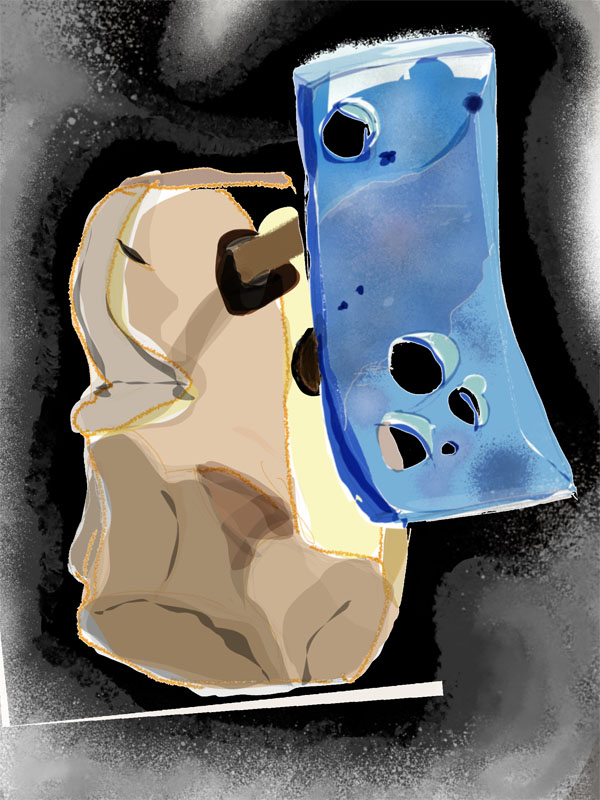

In one such series, rectangular prisms communicated a critical tension in Shaw’s work. I kept returning to the feeling that the form and material of the pieces were at odds with one another, when actually, it was the sensation of encountering something I had never seen in person before.

It reminded me of art historian, Chika Okeke-Agulu, describing his first time seeing the ancient Benin Bronzes in a museum in London: “Being in the presence of these magnificent objects and knowing that I had to travel all the way from Nigeria to see… was a mixture of pride to see these ancient objects, and loss of what could have been...” Algorithms have largely changed this city. I felt privileged to have time and access to NAAM to be in the gallery, but part of that experience is available to you from home. In a Vimeo tour, which I encourage everyone to take, the artist takes us through the exhibition.

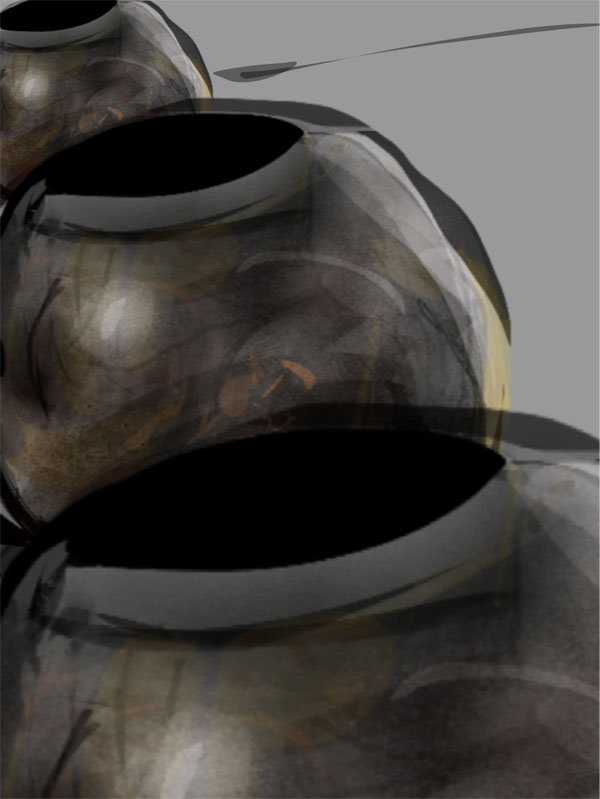

Unblemished spheres showcase a classic treatment of ceramic texture with such fine craft it becomes a geometric expression.

Along with the precision of their shape, the size and density of the vessels portend to their divine energies. If they themselves were not divine, their purpose was, without doubt.

Sometimes after mapping systems, sometimes after disputed places, and sometimes after the limits of space, by how the installations are named we can know that Shaw considered their time, location, and craft in several different languages and disciplines.

Complexity like this should be fatiguing, but Shaw’s design, like patterns repeating and differentiating in a forest, makes an ecology of gestures. The series of monolithic ceramic sculptures appear to be single-utility objects. Shaw’s objects ask us what is made and how things endure in patterned overlap.

When Shaw thinks, the premise considered rises from the ground and spins many times in his hands. That which he thinks through has a longevity evident in its design.

After the dirt, broken ground, is adjoined, it seems the patience of the object to endure, hardening, is burnt into it, leaving almost no trace of maker or tools. But patience itself is a vision of Black art modernity has not valuated highly.

In the case of Divine Guidance, which is where my intrigue first evolved in the gallery, coconut-sized stone spheres sit atop woven bamboo rings. You cannot touch the art but are tempted; all but three structures are displayed without a case. In a cluster of wall-hung stoneware, wild flora springs out lively and hangs, never slouches nor looms.

Shaw’s queries brought up to our inspection, are ground lifted in a holy reversal of dynamic whose terms we can see and understand through the body. To look at Christopher Shaw’s work is to remember the non-magical wonder of alchemy. Lifted, everything is on the table. I cannot stop emphasizing the gesture of exaltation in the way the show was installed.

Though it is possible sometimes to feel as though you are standing within it, the presence of Shaw’s thought is more often like gravity than it is a mass. Thinkers like him create concepts and build our worlds.

The works have such a gravity to them, that while participating in a silent protest in Beacon Hill, as I walked past the museum, all I could hear were footsteps and their echo on the inside of Shaw’s structures as I walked past the museum.

With gratitude for the Coastal Salish Peoples, Kym Littlefield lives in what’s called Seattle, borrowing time from art to art. Along with his own food, Kym makes visual art, jokes, phone calls to older brothers, poetry & Hip Hop.