note from the editor

When I was twenty years old, I remember coming downstairs, home on summer break, and hearing my mom on the phone with a pandit in India. Having become gravely concerned about sister’s future for some reason (my mother was often gravely concerned about at least one of her four children), through the recommendation of her friend, she had gotten the number of a reliable pandit to read my sister’s star chart. I don’t know what the discount rate looks like for family readings, but while on the phone, she asked, absent-mindedly, as she glanced up at me pouring cereal lazily into a bowl, for an assessment of my chart as well.

His report on my sister, the focus of the call, was detailed. Mine was brief but disturbingly accurate: I loved the arts, and would excel as a writer, artist, or fashion designer. I wouldn’t ever make a ton of money, but would have enough to get by, and lastly, but critically: I liked to sleep too much, and I would have to figure out a way to sleep less in order to find success.

The last comment was met by knowing glances when heard by aunts and uncles, especially older ones who remembered me as a child. Back then, almost twenty extended family members had lived in a single family home – and all of the adults had dreaded, and taken turns, waking me in the morning for school. I was a grumpy and stubborn sleeper who would have to be carried out of bed only to fall asleep in the tub during my bath, in a chair while my hair was getting combed and braided, even at the table after breakfast.

In some ways, not much has changed. I struggle to get out of bed, naps are my favorite part of the day, and when I find myself in a warm car on a sunny day, I almost always recline my seat and close my eyes in the parking lot of wherever I have arrived to run errands, even if it means being a little late to a meeting.

I’ve fought against these desires my entire adult life – the words of that pundit, repeated by my mother, rattling around in my brain. What does it mean, I often think, to prefer sleep over being awake? What does it mean to be so content with letting the world, and your short, finite life, pass you by as you stay huddled in blankets, a tiny, tender drool spot staining the cotton of your pillowcase, hair like spilled ink around your face, eyes closed to the world and everything it has to offer?

It took me this year – this life-altering, global-capitalism-rattling, grief-ridden year – to begin to understand that my preference for sleep is not about my lack of desire to be awake; it is about my love of and commitment to dreaming.

I am an anxious person by nature, an overthinker, analytical and obsessive – I find it impossible to let things go (problems, puzzles, grudges) – I get in trouble all the time for trying to solve problems that can’t be solved, or problems that weren’t mine to solve in the first place.

But sleeping. Or the place between being asleep and awake. That liminal plane of fluttering eyelashes, the sun in the window coming in and out of focus, the distant echo of a child laughing in a neighbor’s yard, a sibling singing in the shower – that’s my favorite place. A place where time ceases to exist, and we can begin to imagine all the worlds that could be, should be, would be. If only.

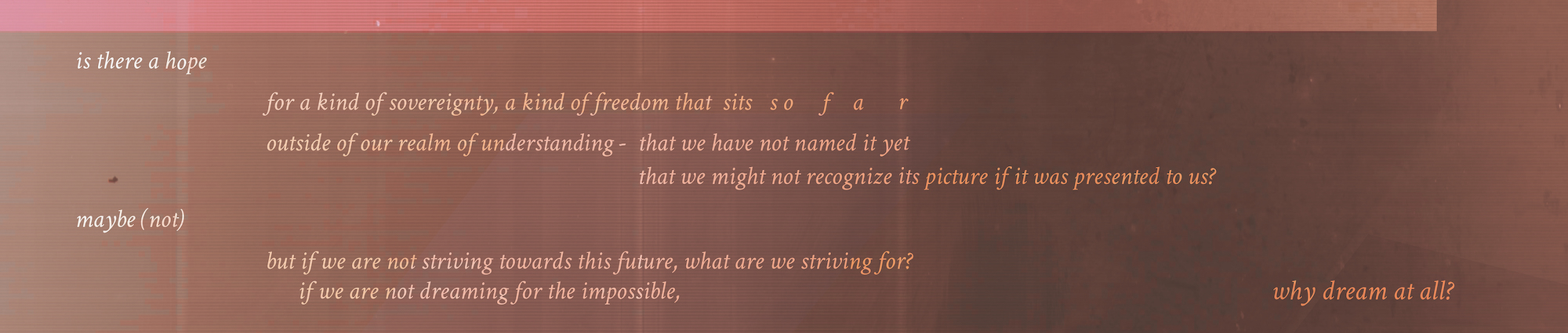

That dreaming. The radical kind that adults are supposed to shake their head at, that even you come to doubt at the end of a long day when nothing seems to change, no one you love seems to win, and you lost another friend cause you sometimes get so caught up in what you think should exist that you forget how to make a certain level of peace with what actually does.

In the spirit of that dreaming, in commitment to the slow and unsteady, meditative and long work that a new kind of world building necessitates, New Archives is leaving Instagram and hesitantly, but hopefully, abandoning the format that we committed to a year ago: three posts a weeks, all of them short – easy to encounter, to read, and to digest.

We never much succeeded at it anyway, as it became clear early on that short and legible has never been mine or Matt’s strong suit. And the grueling, unsustainable pace that we set for ourselves wasn’t ever directed by our desires or those of our community – it was set by the algorithms that the programmers who construct online environments like Instagram dictate. A pace that is focused on overproduction, overconsumption, and a frenetic, dead-eyed scrolling that is designed precisely to make us so unaccustomed to being alone with ourselves that we forget what it means to stare at the ceiling, thinking and bored, until the world as it exists begins to fall away – leaving space for us to imagine things yet unimagined.

It is in an effort to make the work of this publication more conducive to that kind of dreaming that we will be moving to theme-based email newsletter ‘issues’, released at the beginning of every other month, with the longterm goal of releasing them monthly if our lives, and funding, ever allow for it.

We know that this migration off of Instagram will make the regional ubiquitousness that we were initially hoping for when launching New Archives harder to achieve, but we hope that what we lose in terms of visibility and reach will be supplemented by opportunities to be more thoughtful, and to publish longer-form written works that contend deeply with larger, systemic issues affecting the arts in our region.

Because if there’s a choice between ‘success’ and sleep, and we can only dream when we’re sleeping, we choose dreaming. Even if it feels hard, even if we have hesitations, and even if we’re scared. Our lives are finite, and the life of a little arts publication like New Archives is a blip. Who knows how long we will exist. So what do we do with the short, precious time we have been afforded?

We could drag ourselves out of bed, plant ourselves in front of our computers, and try to get by – or we could unplug the alarm, close our eyes, and give ourselves the opportunity to dream of a world that feels at first utterly impossible, entirely frivolous, and then: absolutely urgent and necessary. The kind of world that we could only imagine and create – slowly, circuitously, inefficiently – together.

–Satpreet