Trying to Photograph Perfume

Melanie Flood Projects, Portland

Reading Clarice Lispector’s Água Viva recently, I found myself itching to speak the words aloud, like a spell. I think Lispector meant to give her readers this feeling. “Understand me,” she proclaims, “I write to you an onomatopoeia, convulsion of language. I’m not transmitting to you a story but just words that live from sound.”1 The oral quality of Lispector’s writing enhances her investigation of time, timelessness, and the infinite within the radical present:

I’m trying to seize the fourth dimension of the instant-now so fleeting it’s already gone because it’s already become a new instant-now that’s also already gone. Every thing has an instant in which it is. I want to grab hold of the is of the thing.2

Through variably frenzied, assertive, and somnambulating prose, Lispector works to capture the ineffable. Her mind plunges into the quadrilions of atoms in the universe and seeks meaning for their order and disorder. Her motivation seems to fluctuate between a compulsion and a calculated desire to share and explain what she’s learned with others. Lispector’s words flooded my mind as soon as I walked into Giantess, Rose Dickson’s recent exhibition at Melanie Flood Projects in Portland, OR. Though Dickson told me she hasn’t read Água Viva (yet), the affinities felt undeniable. In paintings, textiles, ceramics, and metal works, Dickson offers a window into the stunning world she has been creating and investigating since adolescence.

Children often enjoy imaginary worlds unencumbered by adult logic or physical probability, but young Rose Dickson took this freedom to a uniquely profound level. Inspired by her stock market analyst-turned-psychiatrist aunt’s stories about Jungian psychology and personality archetypes, four-year-old Dickson began creating a system of symbols to describe the mechanics and metaphysics of her perceived universe.

Today, as an adult, Dickson has refined the system into eight fundamental elements—wood, earth, flame, electricity, ocean, rain, air, and wind—each represented graphically in symbols that appear both ancient and futuristic. Lines twist, curl, and intersect into shapes that give the appearance of belonging to some alphabet, but lack any recognizable referent. Each symbol has its own meaning, and their combinations offer an infinitely nuanced visual language informed by the intuitive connections Dickson makes. If the symbol for wood is above the symbol for ocean, for example, that can mean boat. Ocean over electricity makes an electric eel, and wind over fire signifies flickering.

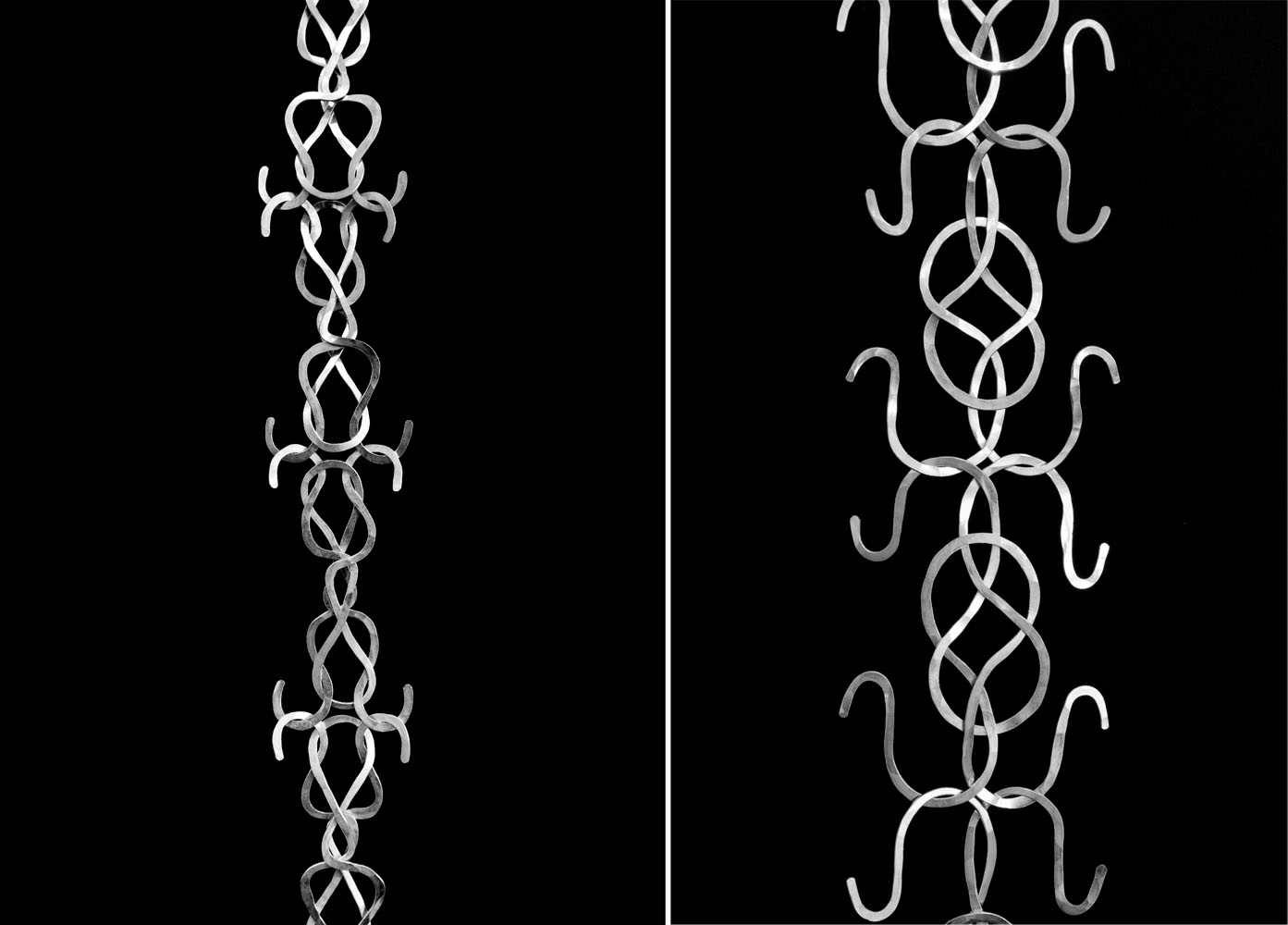

The works in the exhibition, however, don’t reveal any of their secrets. In the first of many interventions, Dickson subtly dictates how her audience can move through the space by hanging several floor to ceiling chains made of interlinked pieces of hammered silver. Each chain becomes an exquisite, delicate column that encourages a more meandering path through the gallery, instead of the typical perimeter walk. Dickson lures visitors into the space by placing her large, hand hooked rug Engine Room (all works 2020) across from the door. The rug features two, four-bladed fans or flowers or wheels—one red, one green—surrounded by beige, overlapping circles on a black background. Each quadfoliate shape has a different symbol on its blade, and two blades intersect in the center of the piece with a single symbol. The visual symbolism and title combine to imply a dynamic object that could rotate to create countless combinations of meaning—yet Dickson explains none of them.

The exhibition as a whole questions the purpose, value, or even possibility of knowing something to be true. I desperately want to know what Dickson’s symbols mean, which I suspect reveals more about me than the symbols themselves. “I trust my own incomprehension that gives me life free of understanding,” writes Lispector. “I don’t want to tell even myself certain things. It would be to betray the is-itself. I feel that I know some truths. Which I already foresee. But truths have no words. Truths or truth?”3

Lispector performs her obsession with the radical present, the “actual perishable instant,”4 in Água Viva through her constant questioning of what she knows and what is knowable. Knowledge, learning, understanding, and doubt are all currents in the broader flow of time. Truth, if it exists, might be found in the infinitely brief, perishable instants of pure being. When one is—only is, not is something—one gains access to the truths within the vacuum of the pure present. I’ve never been there or had that, but I admire anyone pursuing it. “Nothing is more difficult than surrendering to the instant,” writers Lispector, and I wholeheartedly agree.5

Dickson furthers her own pursuit for truth through her elaborate system for finding meaning, yet simultaneously (and rather puckishly) denies her audience any clear answers. Sometimes we get hints in the titles, as with the watercolor and gouache painting Inflection Applies to Speech, But Is Also Seen Here, which features two curly-ended chairs on a wood floor with shadows cast in two opposing directions and a large, symmetrical shape floating between them. I don’t know where inflection can be found in the painting, but by pointing to it, Dickson makes the painting about looking for it. In the more descriptively-titled painting Weather I Remember Applies to Everything, we see various nature scenes painted into sections of two ornate, overlapping shapes. Dickson titled one metal chain A Balance of Power, which seems self-explanatory, while another gets the enigmatically brief title Birch.

Dickson’s titles act as a map through her elaborate labyrinth—one that doesn’t necessarily tell you which turns to take or how to get out, but offers prompts for considering whatever situation we find ourselves in. As Lispector declares, “I do know what I want here: I want the inconclusive. I want the profound organic disorder that nevertheless hints at an underlying order. The great potency of potentiality.”6

Dickson’s gift is in making uncertainty pleasurable—no easy feat in a sociopolitical climate that has weaponized individual and collective doubt. Her system of symbolism and resultant art objects are like sightless hands nimbly reading the frequencies and textures of the world in an attempt to learn their secrets and, most importantly, share them with us. “What I do by involuntary instinct cannot be described,” explains Lispector. “What am I doing in writing to you? Trying to photograph perfume.”7 As with Lispector, Dickson takes the noise, chaos, uncertainty, and immensity of the universe and tries to distill it into something fragrant we can apply to our lives.

- Clarice Lispector, Água Viva (New Yok: New Directions, 2012), 20.

- Ibid., 3.

- Ibid., 47.

- Ibid., 18.

- Ibid., 43.

- Ibid., 20.

- Ibid., 47.

Amelia Rina is a writer and editor based in Portland, OR, on the unceded territories of the Clackamas and Cowlitz nations. In 2020 she founded Variable West, the first platform to provide a comprehensive calendar of art events and exhibitions on the West Coast.