Seamstress

In January 2019, I attended the local poet Lynne Ellis’s chapbook release party at Saint John’s Bar and Eatery on Capitol Hill in Seattle. That lively, crisp, and early-dark night of $3 cans of Rainier, a microphone, and a simple stage of a table and a flatscreen. I was not expecting to leave with a broadside of Ellis’s prize-winning sonnet “Seamstress”, crafted by Felicia Rice, one of the greatest living letterpress artists, of Moving Parts Press. And I was not expecting a near future where artists and their audiences alike could not gather, as we were doing that merry evening, at bars and restaurants for an indefinite time.

I think about fellowship and the necessity for artists to commune with one another and their audience in person. To feel the exchange of ideas flow in the nuances of physical presence is a spirituality of our craft. It is potent, inspiring, and energizing. Even though writers famously prefer to work and be alone, that is a cliche that the Seattle literary community challenges in bars and restaurants around the Puget Sound to great reward. At least, we did until March. I grieve it.

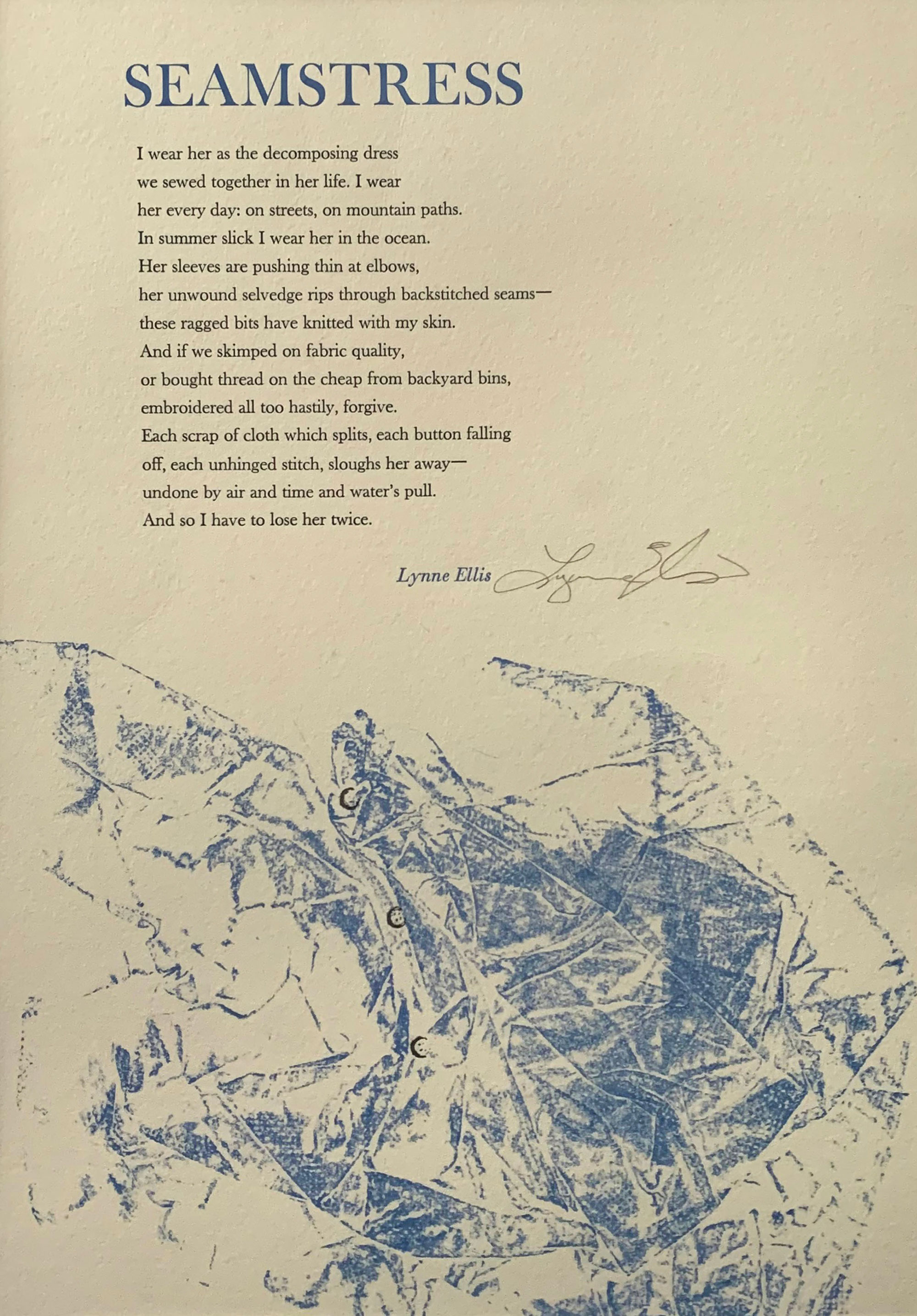

Something about the properties of grief will always be the color blue, but the particular shade chosen by Rice to ink the title of this broadside and the relief print from collotype created with cloth (in the image of a crumpled, collared, button-down shirt) matches how being a Pacific Coast person feels. We are a cliche of sunny beaches and palm trees; in the Pacific Northwest, the brilliance of all shades of green, even in our water. This mixture of light in our water – hues with bases of white or yellow – become the cerulean, or azure, of youth. A lot of the Pacific Coast mythos is wrapped up in a youthful idealism, a feeling that anything can happen here.

And it does. In the poem “Seamstress”, the narrator grieves that second part of loss, when time stretches you far past that once-known horizon – “the decomposing dress / we sewed together in her life” – where your life and the one of the departed was twined and shared; now, the life once shared becomes a singular life, a without-them-here life.

I sit with Ellis and Rice’s collaboration in my living room. Sometimes with my dogs, sometimes with my partner. It is in my kin to honor those who are no longer with us as much as we honor the living in our spaces; this piece feels like a mirror I get to gaze into and see how the state of my moving-on, that new-life-beyond, is developing. These days, I think about those I’ve lost quite a bit.

As the world grieves around me and I grieve the new physical and social landscape as an artist, as an unemployed person, I appreciate the hard pause this broadside of “Seamstress” offers. Grief is a two-part process. It has been and always will be. The assurance of this simple truth, present in my living room, feels much like a buoy as the unknown rages on.

— Christina Montilla

Christina Montilla is a literary artist, floral designer & director of business operations at Mercer Island Florist, and art-appreciator in the Puget Sound region.